Living shorelines as a green/gray option for coastal protection

ABOUT THIS ISSUE

Climate change is resulting in increased coastal hazards due to sea level rise and more intense storms

SOLUTION

Habitat restoration combined with man-made structures, often called “living shorelines”, can be a very effective adaptive approach to coastal protection

Loss/degradation of coastal ecosystems alongside increasing climate change risks in coastal areas

Coastal ecosystems provide many benefits to people, including shoreline protection, support for fisheries, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and opportunities for eco-tourism (Smith et al., 2020). Despite this they have been degraded or lost in many areas worldwide. Considering the impacts of climate change on coastal areas, it is essential to restore these ecosystems, and consequently their benefits, as much as possible. Living shorelines provide one option for restoring some of these benefits, particularly coastal protection services.

Living shorelines as an adaptation option

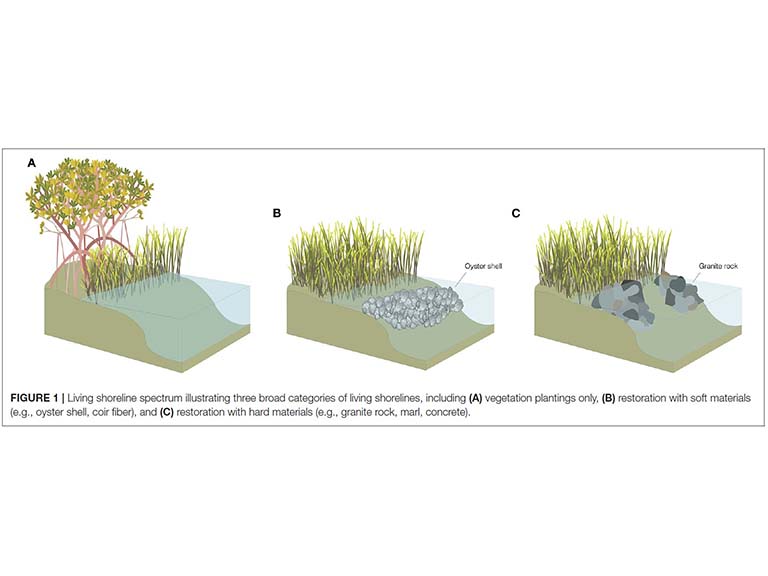

The term “living shorelines” typically refers to shoreline protection approaches that incorporate habitat restoration, alone or in combination with some type of built infrastructure, to provide coastal protective services to humans (NOAA, 2015). These approaches can be categorized along a green to gray continuum, ranging from purely vegetative plantings on the green end, to habitat restoration in conjunction with the addition of structural materials on the gray end (Smith et al., 2020; see Figure 1 for examples). One notable characteristic of living shorelines is that they have the potential to provide social, ecological, and economic benefits. For example, they can protect shorelines from coastal hazards, help cycle nutrients, support fisheries, promote (eco)tourism, and sequester carbon (Smith et al., 2020).

A recent study identified 46 cases of living shorelines interventions (projects) around the world and analyzed their geographic characteristics, design characteristics, and outcomes (Smith et al., 2020). Here, the main findings of this study are explained, as they are useful to understand the potential of living shorelines as an NbS in coastal areas.

Characteristics of living shorelines projects

82% of the living shoreline projects identified were in North America, with the remainder in Asia (11%) and Europe (7%). Thus, there currently seems to be a lack of living shorelines interventions outside North America, although this could partly be because only English language literature was searched in the study.

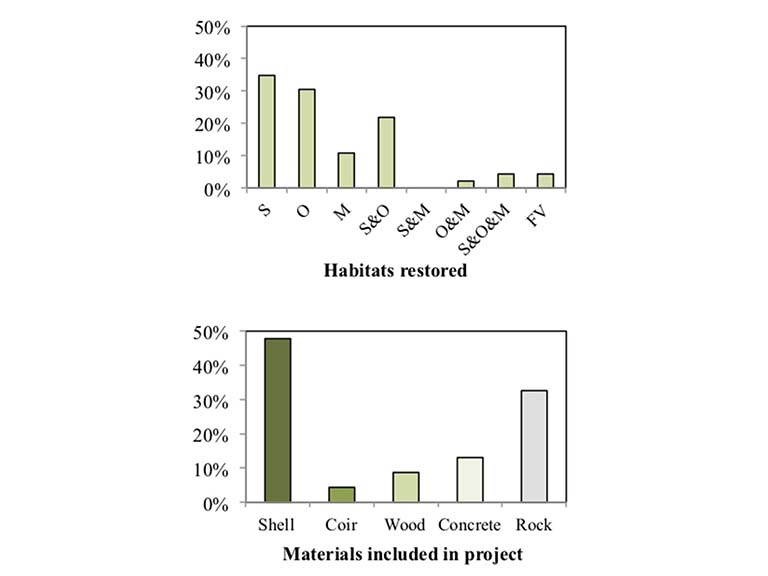

Figure 2 shows the main types of habitats restored and materials used (in addition to vegetation). Most interventions involved restoring salt marshes and oyster reefs, mangrove habitats were a distant third, and most incorporated shells and rock in their design as breakwaters to reduce wave energy (thus reducing impacts of waves on the shoreline). These findings highlight that living shorelines may be particularly useful in coastal areas with degraded salt marsh, oyster reef, or mangrove habitats. Materials for breakwaters can be collected from natural sources, e.g., shells, rocks, wood, or coir logs. Alternatively, concrete can be used.

Remaining knowledge gaps regarding living shorelines as an NbS

The study noted several knowledge gaps that remain with regards to living shorelines as a coastal NbS. Some of the main points are as follows:

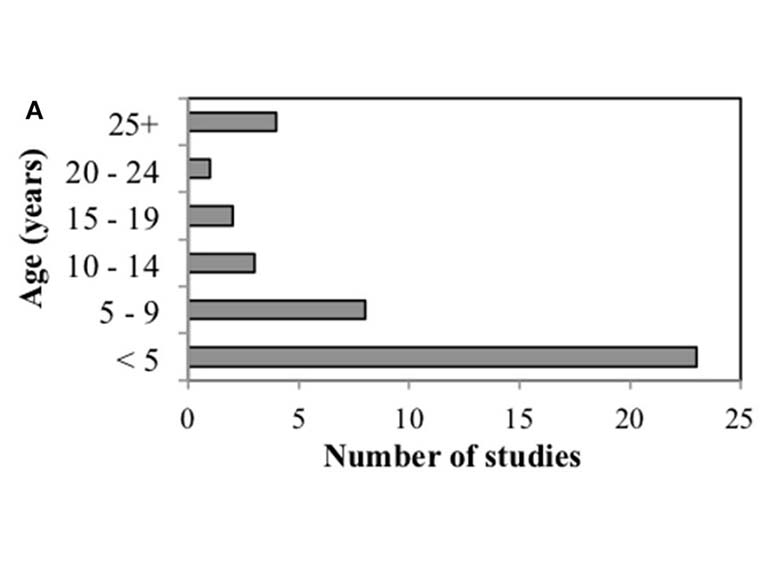

- The long-term performance and maintenance costs of living shorelines compared to conventional hard infrastructure are still relatively uncertain. Most living shoreline projects analyzed in the literature were less than 5 years old (Figure 3).

- More research is needed to better understand how different living shoreline designs and materials affect the social/economic/ecological benefits they provide in different environmental contexts. For example, different designs/materials may be preferable in mangrove habitats than in salt marsh habitats. To better understand this, comparison case studies need to be carried out.

Main points for planners and policymakers

- Living shorelines can potentially provide an effective NbS for mitigating coastal hazards while also providing various social and ecological benefits.

- There is a lack of studies on the long-term cost effectiveness of living shorelines. There is also no information regarding which materials are more effective as breakwaters in different environmental contexts. Thus, to minimize the initial and follow-up costs of living shorelines, it would be most efficient to use materials that are readily available locally (e.g., shells, rocks, or wood, depending on the site).

References

- NOAA (2015). Guidance for Considering the Use of Living Shorelines. (accessed January 06, 2022).

- Smith, C. S., Rudd, M. E., Gittman, R. K., Melvin, E. C., Patterson, V. S., Renzi, J. J.,et.al. Silliman, B. R. (2020). Coming to terms with living shorelines: A scoping review of novel restoration strategies for shoreline protection. Frontiers in Marine Science, Vol. 7, pp. 1–14.